Opinion: CNN And CNBC Turn The News Into Vegas Slot Machine By Partnering With Kalshi

There are moments when the media world gently shifts. Then there are moments like this one, when CNN looks at the global collapse of trust in journalism and says, essentially, “What if we made the news a little more… bettable?”

Because that’s exactly what’s happening.

CNN has entered a glossy, data-soaked partnership with Kalshi—a prediction market where people literally gamble on real-world events—and soon you’ll be seeing its real-time “odds” woven into CNN’s reporting, tickers, graphics, and analysis.

- CNN and CNBC partner with Kalshi to embed real-time prediction market odds into news, blending journalism with financial speculation.

- Kalshi’s contracts were ruled gambling under state law, raising regulatory risks as courts and authorities scrutinize the platform.

- This shift risks warping journalism by tying news coverage to market outcomes, creating conflicts of interest and press freedom threats.

CNBC promptly followed with its own multi-year deal. At this point, the only thing missing is Anderson Cooper lighting a cigar and saying, “Place your wagers, folks.”

CNN entered a partnership with Kalshi. Image credits: Brandon Bell/Getty Images

The networks frame this as innovation. Viewers, critics, academics, gambling regulators, basically anyone with a functioning moral compass, call it something else entirely: a slow-motion demolition of journalistic independence wearing the trench coat of “data-driven analysis.” What we’re really watching is the beginning of casino-fied news. And the worst part? We kind of knew it was coming.

The collision of journalism and betting markets

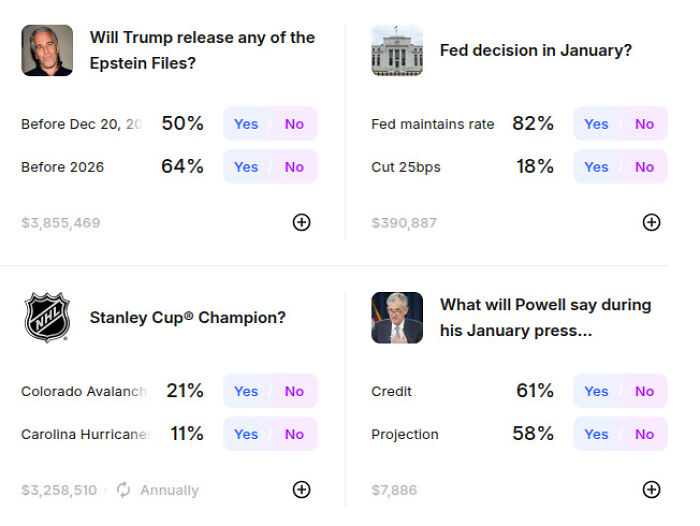

Kalshi, for the uninitiated, is a platform where users put real money behind predictions about real-world events. Will inflation go up? Will a hurricane hit? Will Congress accidentally set democracy on fire again next Tuesday?

People trade contracts on these questions the way traders buy futures on soybeans. Kalshi insists this is not gambling, that these are “financial instruments.” But last month, a Nevada federal judge gently (okay, loudly) disagreed, ruling that Kalshi’s contracts fall under state gambling laws.

That ruling shook the industry because the minute courts call you out for gambling, regulators with clipboards appear out of the bushes like Pokémon. Kalshi has appealed, so it remains to be seen whether the platform will be forced to shut down some operations or whether a higher court will overturn or limit that ruling.

Co-founder and CEO of Kalshi, Tarek Mansour. Image credits: Diarmuid Greene/Sportsfile for Web Summit via Getty Images

So what do you do when regulators are circling? You grab a microphone the size of CNN and say, “Hey, show everyone our data every hour of every day.” It’s a brilliant strategy, in a shark-in-a-suit kind of way. Get the biggest legacy news network to treat your odds as legitimate “information,” and suddenly your legal problems start to look like boring paperwork, not existential threats.

CNN gets “cool new analytics.” Kalshi gets free legitimacy. And the public gets a slow infiltration of gambling logic into everyday news. Nobody wins except the people who were already winning.

The allure of turning the news into a game

There’s a seductive psychology at work here. News is exhausting. Politics is exhausting. The world, in general, is exhausting. So naturally, the idea of turning the oncoming collapse of civilization into something you can trade like a baseball statistic feels… manageable. Comforting, even.

Image credits: Kalshi

The networks have leaned into this. They present Kalshi’s predictions as a kind of “wisdom of the market,” a crowdsourced forecast of what’s coming. This is apparently better than “legacy analysis” or “expert opinion,” because the people trading these contracts allegedly have skin in the game. (As if that has ever stopped anyone from being wrong in spectacular and expensive ways.)

It’s unclear whether every type of contract will be treated the same or news-oriented contracts will escape regulation.

But making the news “interactive” through prediction markets fundamentally changes the way audiences perceive information. Instead of events being covered because they matter, events begin to matter because they can be wagered on. That’s content arbitrage, and it has a long and painful lineage.

When corporate partnerships changed the news before (and not for the better)

Media history is littered with corporate alliances that reshaped journalism in ways we’re still living with. The CNN–Kalshi and CNBC–Kalshi partnerships fit squarely into that tradition, except now we’re adding gambling logic to the mix. Cute.

Think of the seismic shift that came with the birth of 24-hour news. When CNN launched in 1980, it revolutionized the industry. But it also created the monster we now call “breaking news” culture; that hyperventilating cycle where everything is urgent, nothing is contextualized, and the news exists in a permanent state of caffeinated chaos. It changed what counted as news, and, more importantly, how fast it needed to appear.

Then came the Murdoch era, where the media didn’t just report politics. It was manufactured. Fox News helped build a whole political identity, one that consumed and pumped its own narratives in a closed loop. News became a political actor, not an observer.

Fast-forward to Bloomberg, where financial data and journalism merged so thoroughly that it became impossible to tell where one ended and the other began. Bloomberg’s model worked because traders already lived in regulated markets. But even there, critics warned that the tight fusion of information and financial interest carried risks.

Media mogul Rupert Murdoch. Image credits: Victoria Jones/PA Images via Getty Images

Then came the algorithmic age. Newsrooms contorted themselves to obey the whims of social media: chasing clicks, outrage, and concentrated engagement like addicts hunting a fix. When Facebook tweaked its algorithm, entire companies folded. When Twitter amplified misinformation at scale, news organizations trailed behind like exhausted parents trying to stop a toddler from setting themselves on fire.

And let’s not forget the native advertising era, where “sponsored content” infiltrated articles so thoroughly you needed a degree in forensic linguistics to work out if the reporter actually wrote it or if Big Mattress did.

None of these partnerships were pitched as nefarious. Every one of them were sold as innovation. And every single one, in their own way, chipped away at journalism’s ability to stand apart from the interests shaping it.

The difference this time is we’re not just merging news with corporate power. We’re merging news with financial speculation on the outcomes of the stories being reported. If you think that’s not going to warp coverage, I have a lovely bridge to sell you at Kalshi’s newly predicted 87% chance of somebody believing this.

The road not taken: Remember Good Judgment?

Before CNN decided to cosplay as a Vegas sportsbook, there actually was a perfectly respectable, research-backed way to bring probability into journalism: Good Judgment. Yes, the same Good Judgment that grew out of Philip Tetlock’s famous forecasting tournament. The one that proved a handful of spreadsheet enthusiasts, schoolteachers, engineers, and statistically literate introverts could outperform intelligence agencies with billion-dollar budgets. If the CIA were the Death Star, these people were the Ewoks with graphs.

See what our Superforecasters expect in the coming year with @TheEconomist‘s future-gazing guide, The World Ahead 2026! https://t.co/X4unPVWJ3I

— Good Judgment Inc (@superforecaster) November 12, 2025

Good Judgment became the gold standard for serious, non-gamified forecasting. Their “superforecasters” were trained to think critically, avoid cognitive traps, and, crucially, not put money on whether democracy could collapse before Friday. They provide probability estimates to governments, corporations, and NGOs without the faint background hum of a slot machine. And if a news organization wanted to incorporate responsible probabilistic thinking into its coverage, partnering with Good Judgment would have been the obvious choice. High credibility, low controversy, zero roulette wheels.

And that’s why critics keep bringing them up in the CNN/Kalshi discourse. Because the alternative path was right there: Calm, evidence-based forecasting, transparent, academically grounded methodology, no cash incentives to manipulate outcomes, and no “bet on whether Congress survives the week” aesthetic.

But instead of choosing the method that beat intelligence agencies in forecasting accuracy, CNN chose the financial equivalent of “what if Wall Street had a baby with a sports book?” The point isn’t that Good Judgment is perfect; it’s that it exists, it’s respected, and it doesn’t require viewers to open an account, link a bank card, and gamble on geopolitics.

So when people say the CNN/Kalshi partnership feels reckless, what they really mean is: The grown-up option was right there—and CNN still ordered the tequila flight.

When news becomes a participant rather than an observer

Here’s where it gets genuinely troubling. Once CNN integrates Kalshi’s odds into its reporting, the network becomes part of the very mechanisms that determine those odds. Kalshi’s markets move when information moves. CNN produces information. This is not a cute circularity. It’s a structural conflict of interest.

Image credits: Kalshi

Imagine a world where covering a political scandal doesn’t just inform the public; it immediately shifts odds in a marketplace. Imagine the subtle incentives that it creates to keep stories “alive,” to emphasize volatility, to avoid reporting anything that would stabilize the markets. Volatility becomes a product. Uncertainty becomes currency. And news becomes a performance.

Even if every journalist in the building swears they’re ethically pure (bless their hearts), the structural incentives will still warp coverage. Because once you tie journalism to a market like this, you don’t just risk conflicts of interest: you bake them into the architecture of the newsroom, endangering press freedom.

Press freedom, the endangered species, takes another blow

Press freedom dies in many ways; sometimes with censorship, sometimes with violence, and sometimes with a long, slow slide into compromised incentives. Linking news coverage to prediction markets is a quiet, elegant way to do the latter.

If the news becomes financially tied to a platform currently being scrutinized by gambling regulators, political actors gain leverage over it. If regulators start closing in on Kalshi, CNN and CNBC risk being dragged along for the ride. That’s the kind of entanglement governments love, because it creates opportunities to pressure, punish, or manipulate news outlets without ever passing a law.

CNN partners with Kalshi to integrate prediction markets into its global newsroom.

The first major news network to embrace Kalshi prediction markets.

A new era of media is here. pic.twitter.com/uXLlWVLjQs

— Kalshi (@Kalshi) December 3, 2025

Meanwhile, public trust (already at record lows) will almost certainly erode further. Once viewers sense that odds are moving alongside the stories, suspicion becomes baked in. Did coverage influence the odds? Did the odds influence coverage? Is the news reporting reality, or is it reporting what will generate the most dramatic market movement? In a world where conspiracy theories are already hydrating themselves like plants in summer, this is adding Miracle-Gro.

And then there’s the political angle. Imagine campaigns using prediction markets to strategically amplify rumors, knowing that a spike in trading contracts will push networks to cover them. Imagine wealthy actors quietly betting on outcomes they privately help engineer. Imagine news segments becoming inadvertent vehicles for market manipulation. Actually, you don’t need to imagine it. We’ve already watched versions of that happen with social media.

The real horror: We’re getting used to this

What genuinely worries me is how unsurprising this all feels. We live in a world where everything—news, culture, politics, and even tragedy—has been fed through the content machine so many times that it’s hard to shock anyone. CNN partnering with a betting platform? Oh sure. That seems about right for 2025. It’s been a long year, and we’re not even done.

This numbness is dangerous. It’s what allows slippery changes to slide into permanence. It’s what lets newsrooms quietly rebrand gambling as “data,” and what lets corporations push into journalism with the confidence of men who have never been told no.

Newsrooms have already contorted themselves to obey the whims of social media. Image credits: Matt Cardy/Getty Images

The worst part: the networks will justify this as a way to “engage younger viewers.” As if the only way to get Gen Z to care about the world is to turn the news into a slot machine.

Spoiler: if the future of journalism depends on tricking 19-year-olds into watching the odds on a natural disaster, maybe the problem isn’t the youth. Maybe the problem is journalism’s refusal to imagine a future not built out of spectacle.

So what now?

What happens next depends on how loudly people push back. It depends on whether regulators keep tightening their grip, and whether news consumers are willing to say, “Actually, I would like my journalism un-gamified, thank you very much.”

Because if this sticks, if prediction-market data becomes a standard news feature, the next decade will look very different. News will become less about informing the public and more about monetizing uncertainty. The newsroom will become a pressure cooker of incentives that serve markets, not audiences. And public trust, that already-fractured little bird, will get hit by a bus.

This isn’t alarmism. This is pattern recognition. We’ve spent decades watching journalism bend toward profit, spectacle, outrage, and algorithmic favor. Kalshi is not the beginning of that story. It is the logical endpoint. When the news becomes a place where you watch the probability of a government shutdown change in real time, democracy becomes a spectator sport with betting odds. And we all know, the house always wins.

Poll Question

Thanks! Check out the results:

1k+views

Share on Facebook

15

0