The Trump administration is reportedly preparing a fresh escalation against Nicolás Maduro’s Venezuela, widening a militarized anti-drug campaign that has already seen U.S. forces strike dozens of suspected trafficking vessels in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific – attacks the White House has repeatedly cast as a blow against the fentanyl trade.

- The Trump administration is reportedly preparing a fresh military escalation against Venezuela.

- Experts say South America, including Venezuela and Colombia, plays no significant role in fentanyl supply to the U.S., which mainly originates in Mexico.

- Fentanyl precursors mostly come from China and are shipped to Mexico through Pacific routes, avoiding Colombia and Venezuela as significant transit points.

- Mexican cartels synthesize fentanyl in small, mobile labs, making the drug supply resilient to enforcement efforts.

“If you’re on a boat full of cocaine or fentanyl … headed to the United States, you’re an immediate threat to the United States,” said U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio on September 4, three days after the first strike killed 11 people.

Eleven days later, after a second strike that left three dead, President Donald Trump doubled down. “We have proof … the cargo that was spattered all over the ocean, big bags of cocaine and fentanyl,” Trump told reporters at the White House on September 15.

Donald Trump has doubled down on the boat strikes. Image credits: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

To date, 21 strikes against boats departing from the Colombian and Venezuelan coasts have killed at least 69 people, according to Reuters.

The fentanyl framing taps into deep U.S. fears: synthetic-opioid overdoses have claimed roughly 450,000 lives over the past decade. Yet neither country fits into the supply chain in a meaningful way.

The precursor highway: China to Mexico

“The fentanyl trade has absolutely nothing to do with South America, including Venezuela, Colombia, or the Caribbean,” said John Walsh, director for drug policy and the Andes at the Washington Office on Latin America. “The illicit fentanyl manufacturing that supplies North America mostly originates in Mexico using precursors that mostly come from China.”

After Beijing scheduled all fentanyl-related substances in 2019, suppliers pivoted away from mailing finished fentanyl and toward selling precursor and “pre-precursor” chemicals online.

The U.S.S. Gerald R. Ford has been deployed to the Caribbean. Image credits: Alyssa Joy/U.S. Navy via Getty Images

Many precursors are chemicals with legitimate industrial roles, making them harder to control than a finished narcotic. International regulators only schedule a narrow set of core fentanyl precursors, so traffickers can substitute close chemical relatives or tweak recipes if a particular molecule is restricted.

Brokers and front companies move those chemicals through regular maritime and air cargo to Mexico, typically via Pacific ports and sometimes routed through third countries to disguise origin – though public reporting does not point to Colombia or Venezuela being significant third country destinations. The same procurement networks ship pill presses and die molds used to turn fentanyl into counterfeit tablets.

The International Narcotics Control Board reports that Mexico and the United States are now the only countries regularly seizing controlled fentanyl precursors, a sign that illicit manufacture is concentrated in North America rather than farther south.

Synthetic-opioid overdoses have claimed roughly 450,000 lives over the past decade. Image credits: VCG/VCG via Getty Images

Mexican networks – especially the Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco New Generation Cartel – synthesize fentanyl in compact labs that can be moved or rebuilt quickly, making supply resilient.

“These labs are tiny things. They’re nimble and quick. The idea that destroying them, even a lot of them in a small period of time, could make a significant difference in supply is just not the case,” Walsh said.

Mexico to U.S. ports of entry, then street markets

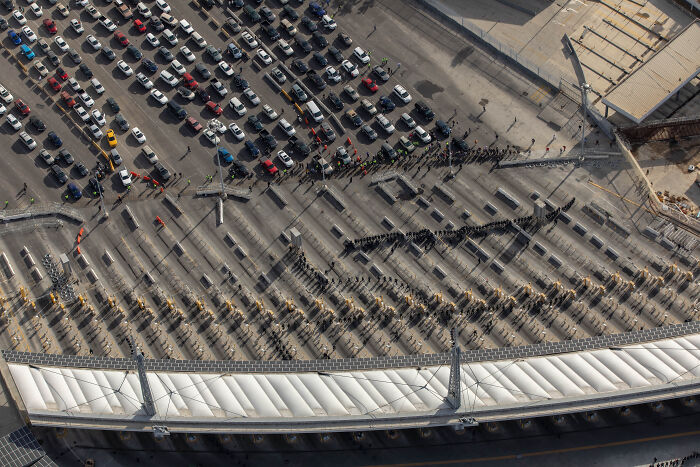

“Over 85% of people sentenced for fentanyl trafficking are U.S. citizens, and most trafficking takes place through ports of entry,” said Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, head of the North American Observatory at the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, in an email.

Most trafficking takes place through ports of entry. Image credits: CBP Photography, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Because a few kilograms translate into millions of doses, traffickers don’t rely on bulky loads to hide consignment; the everyday commercial and passenger flow across the U.S.-Mexico border is the ideal vector. Authorities most often intercept fentanyl hidden in passenger vehicles, blended into legitimate truck or container loads, or mailed in small parcels.

That reflects a transnational business model: Chinese suppliers and Mexican producers rely on U.S. retail partners, while laundering networks recycle profits through banks, remitters, shell companies and crypto rails.

For Farfán-Méndez, enforcement has to be binational and financially literate – following procurement chains and targeting laundering – alongside harm-reduction measures that cut deaths even when supply persists.

Authorities most often intercept fentanyl hidden in passenger vehicles. Image credits: CBP Photography, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“If the goal is to save lives, and I agree this should be a priority objective, evidence shows that harm reduction approaches in fact reduce excess mortality and are also cost effective,” she wrote.

South America not a fentanyl corridor

In Colombia, while fentanyl and other synthetic opioids do find their way into local drug markets, they are usually adulterants added to other psychoactive substances, according to Medellín-based public-health researcher Sebastián Tamayo Salinas.

“If we had a big fentanyl market, we would have many overdose deaths,” he said.

Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro. Image credits: Jesus Vargas/Getty Images

Local and regional monitoring lines up. In an October 2025 report from Colombia’s Justice Ministry on the chemical composition of psychoactive substances, no groups of drugs were found to be adulterated with fentanyl or other synthetic opioids to significant degrees.

Meanwhile, a December 2024 Brookings report found illicit fentanyl distribution in South America remains very low, with rising seizures mostly tied to leakage from medical facilities and only scattered cases of fentanyl-adulterated drugs.

In Colombia, authorities recorded a steep rise in seized medical fentanyl vials after 2021, but there is no evidence of entrenched illegal production networks.

“In Colombia, we do not have the technical or technological tools to produce fentanyl… Fentanyl requires high technology to be able to make it… [here] there are no laboratories producing it,” said Tamayo.

Meaning, whatever those boats are carrying, fentanyl isn’t a credible reason to bomb them, nor to escalate military engagement with Venezuela.

Poll Question

Thanks! Check out the results:

1k+views

Share on FacebookTrump just flat makes things up to try to lull his sheep into adoring him and supporting him. It's sick.

Trump just flat makes things up to try to lull his sheep into adoring him and supporting him. It's sick.

16

1